Ship of fools

The ship of fools (Modern German: Das Narrenschiff, Latin: Stultifera Navis), is an allegory, first appearing in Book VI of Plato's Republic, about a ship with a dysfunctional crew. The allegory is intended to represent the problems of governance prevailing in a political system not based on expert knowledge.

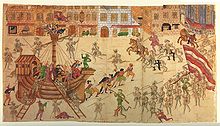

Images of the ship became popular, especially in German-speaking lands, especially after the publication of Sebastian Brant's satirical book Ship of Fools (1494), which served as the inspiration for Hieronymus Bosch's painting, Ship of Fools. Normally, the images show a ship crowded with men mostly wearing traditional jester or fool's costume with cloth ears ending in bells, many quarreling, drinking, and fighting. In the book a ship—an entire fleet at first—sets off from Basel, bound for the Paradise of Fools. In it, Brant conceives Saint Grobian, whom he imagines to be the patron saint of vulgar and coarse people. In literary and artistic compositions of the 15th and 16th centuries, the cultural motif of the ship of fools also served to parody the "ark of salvation", as the Catholic Church was styled.[citation needed]

A "complex political satire", whose composition was repeated in at least seven different 15th-century prints, indicating great popularity, shows Pope Paul II and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III wrestling at the top of a ship's mast, wearing only briefs and their respective Papal tiara and crown. Emblems and labels cover many other European powers; the allegory is of the political fall-out from meetings between the two men in 1468-69.[1]

After the Protestant Reformation, some depictions took a sectarian turn. A woodcut illustration to an edition of 1584 of Brant's book shows the Anti-Christ sitting on top of the overturned Narrenschiff, while in the foreground Saint Peter guides a small boat of respectably-dressed men safely to shore.[2]

"Ship of Fools" has continued to be used into the 20th century as the title for numerous books, songs and other works. Some German cities have modern public sculptures of the subject: a fountain by Jürgen Weber in Nuremberg (1980s), a sculptural group in Neuenburg am Rhein (2004), a fountain in Cologne, and one in Bräunlingen of the shipwrecked boat.

Benjamin Jowett's translation of Plato's text

[edit]

Benjamin Jowett's 1871 translation recounts the story as follows:

Imagine then a fleet or a ship in which there is a captain who is taller and stronger than any of the crew, but he is a little deaf and has a similar infirmity in sight, and his knowledge of navigation is not much better. The sailors are quarrelling with one another about the steering -- every one is of opinion that he has a right to steer, though he has never learned the art of navigation and cannot tell who taught him or when he learned, and will further assert that it cannot be taught, and they are ready to cut in pieces any one who says the contrary. They throng about the captain, begging and praying him to commit the helm to them; and if at any time they do not prevail, but others are preferred to them, they kill the others or throw them overboard, and having first chained up the noble captain's senses with drink or some narcotic drug, they mutiny and take possession of the ship and make free with the stores; thus, eating and drinking, they proceed on their voyage in such a manner as might be expected of them. Him who is their partisan and cleverly aids them in their plot for getting the ship out of the captain's hands into their own whether by force or persuasion, they compliment with the name of sailor, pilot, able seaman, and abuse the other sort of man, whom they call a good-for-nothing; but that the true pilot must pay attention to the year and seasons and sky and stars and winds, and whatever else belongs to his art, if he intends to be really qualified for the command of a ship, and that he must and will be the steerer, whether other people like or not, the possibility of this union of authority with the steerer's art has never seriously entered into their thoughts or been made part of their calling. Now in vessels which are in a state of mutiny and by sailors who are mutineers, how will the true pilot be regarded? Will he not be called by them a prater, a star-gazer, a good-for-nothing?[3]

References

[edit]- ^ Jay A. Levinson (ed.) Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), 1973, pp. 162-164 (162 quoted), LOC 7379624; Mark McDonald, Ferdinand Columbus, Renaissance Collector, p. 100, 2005, British Museum Press,ISBN 978-0-7141-2644-9

- ^ Library of Congress

- ^ Jowett, Benjamin (1871). The Republic by Plato.