Piano Sonata No. 29 (Beethoven)

| Piano Sonata No. 29 | |

|---|---|

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

Beethoven in 1818–19; portrait by Ferdinand Schimon | |

| Other name | Hammerklavier |

| Key | B-flat major |

| Opus | 106 |

| Composed | 1817 |

| Published | 1818 |

| Duration | 40–45 minutes |

| Movements | 4 |

The Piano Sonata No. 29 in B♭ major, Op. 106 (known as the Große Sonate für das Hammerklavier, or more simply as the Hammerklavier) by Ludwig van Beethoven was composed in 1817 and published in 1818. The sonata is widely viewed as one of the most important works of the composer's third period, a pivotal work between his third and late period,[1] and among the greatest piano sonatas of all time. It is also considered to be Beethoven's most technically challenging piano composition and one of the most demanding solo works in the classical piano repertoire. The first documented public performance was in 1836 by Franz Liszt in the Salle Erard in Paris to an enthusiastic review by Hector Berlioz.[2]

Background

[edit]Prior to the creation of the Hammerklavier sonata, the year between 1807 and 1812 were considered one of Beethoven's most productive period. During that time, he composed four symphonies (No. 5 through 8), three piano sonatas (opp. 78-81a), the Piano Concerto No. 5, "Emperor", the Mass in C major, and various chamber works. After the period, his output reduced drastically, although scholars disagreed on when this period of decline started, with proposed start date ranging from 1812 to 1816.[3]

The earliest sketches for the sonata is likely dated from December 1817,[4] although the original manuscript is lost.[5] Amongst the sketches for the first movement is an idea for an abandoned cantata for Archduke Rudolph, using the text ‘Vivat Rudolphus’ and a melody resembling that of the ‘Hammerklavier’.[6] The sonata was planned from the beginning to be a tribute to Archduke Rudolph. This intention was confirmed in Beethoven’s letter of 3 March 1819, in which he says that the sonata had long been ‘wholly intended in my heart’ for the archduke.[4] The process of its creation was considered the longest of any of his piano works, and it ushered in a period during which Beethoven tackled large-scale works such as the Missa Solemnis, the Ninth Symphony, and the Diabelli Variations.[7] Musicologist William Kinderman attributed this to his preoccupation with his nephew Karl von Beethoven, his health problems,[1] and an increasing focus on each of his major new compositions, usually large-scale works.[8]

The sonata was planned to publish in 1819 in Vienna and London with the support of Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s friend and former pupil, who had arranged for a London edition to be published about the same time as the planned Viennese edition by Artaria.[9] The Vienna edition is published in October 1819, while the London edition is published in December of the same year,[10] with a dedication to Antonie Brentano instead of Archduke Rudolph of the Vienna edition.[11] The London edition of the sonata is published in two parts: the first part has the first three movements with the second and third movement in reversed order, and the second part is the fourth movement.[12] The reason for this rearrangement is purely economical, as Charles Rosen believes Beethoven’s sole concern for publishing the sonata in London was to obtain financial benefit.[13]

The nickname Hammerklavier originates from Beethoven’s desire to use German terms to replace Italian terms in a “burst of patriotic enthusiasm”, as “Hammerklavier” is the German term for the pianoforte.[14] In a letter to Sigmund Anton Steiner on January 23, 1817, Beethoven states: “henceforth on all our works...insted of pianoforte Hammerklavier is used”.[15] Only the Sonata No. 28 in A major, Op. 101, and the Sonata No. 29 is published as "für das Hammerklavier" ("for the piano"),[15] and over time the nickname has become associated with the latter.[16][3]

Structure

[edit]The piece contains four movements, a structure used by Beethoven in his earlier piano sonatas. However, the order of the inner movements are reversed, with the Scherzo placed before the Adagio sostenuto.[17]

In addition to the thematic connections within the movements and the use of traditional Classical formal structures, Charles Rosen has described how much of the piece is organised around the motif of a descending third (major or minor).[18] (Carl Reinecke had first remarked on this in 1897).[19] This descending third is quite ubiquitous throughout the work but most clearly recognizable in the following sections: the opening fanfare of the Allegro; in the scherzo's imitation of the aforementioned fanfare, as well as in its trio theme; in bar two of the adagio; and in the fugue in both its introductory bass octave-patterns and in the main subject, as the seven-note runs which end up on notes descended by thirds.

The Hammerklavier also set a precedent for the length of solo compositions (performances typically take about 40 to 45 minutes). While orchestral works such as symphonies and concerti had often contained movements of 15 or even 20 minutes for many years, few single movements in solo literature had a span such as the Hammerklavier's third movement.

Tempo

[edit]The sonata is the only sonata for which Beethoven provided metronome marks, given that the metronome had been patented by Johann Maelzel in 1815, and Beethoven was among the first composers to use the device.[20] The metronome mark was given at the beginning of a letter to Ferdinand Ries, dated 16 April 1819, that states the tempo of 138 BPM on the half note for the first movement.[21] This is considered so fast that it is routinely dismissed by performers based on theories that it was caused by a mistake from the composer, a faulty metronome, or Beethoven's deafness.[22] Suggestions for revisions have come from Felix Weingartner, Ignaz Moscheles and Paul-Baruda Skoda.[23]

I. Allegro

[edit]

The first movement in B♭-major, marked Allegro, opens with a series of fortissimo B♭-major chords, which form much of the basis of the first subject. After the first subject is spun out for a while, the opening set of fortissimo chords are stated again, this time followed by a similar rhythm on the unexpected chord of D major.[24] This ushers in the more lyrical second subject in the submediant (that is, a minor third below the tonic), G major.[25] A third and final musical subject follows, which exemplifies the fundamental opposition of B♭ and B♮ in this movement through its chromatic alterations of the third scale degree. The exposition ends with a largely stepwise figure in the treble clef in a high register, while the left hand moves in an octave-outlining accompaniment in eighth notes.

The development section opens with a statement of this final figure, except with alterations from the major subdominant to the minor, which fluidly modulates to a fugue in E♭ major.[26] The fugato ends with a section featuring non-fugal imitation between registers, eventually resounding in repeated D-major chords. The final section of the development begins with a chromatic alteration of D♮ to D♯. The music progresses to the alien key of B major, in which the third and first subjects of the exposition are played. The retransition is brought about by a sequence of rising intervals that get progressively higher, until the first theme is stated again in the home key of B♭, signalling the beginning of the recapitulation.

There is debate whether A-sharp or A-natural should be played in measures 224-26, which is at the end of the development.[27][28]

In keeping with Beethoven's exploration of the potentials of sonata form, the recapitulation avoids a full harmonic return to B♭ major until long after the return to the first theme. The coda repetitively cites motives from the opening statement over a shimmering pedal point and disappears into pianississimo until two fortissimo B♭ major chords conclude the movement.

II. Scherzo: Assai vivace

[edit]

The brief second movement includes a great variety of harmonic and thematic material. The scherzo's theme – which Rosen calls a humorous form[29] of the first movement's first subject – is at once playful, lively, and pleasant. The scherzo, in B♭ major, maintains the standard ternary form by repeating the sections an octave higher in the treble clef.[30]

The trio in B♭ minor, marked "semplice", is in binary form.[30] It borrows the opening theme from the composer's Eroica symphony and places it in a minor key. Following this dark interlude, Beethoven inserts a more intense presto section in 2

4 meter, still in B♭ minor,[31] which eventually segues back to the scherzo, marked "dolce".[30] After a varied reprise of the scherzo's first section, a coda with a meter change to cut time follows. This coda plays with the semitonal relationship between B♭ and B♮, and briefly returns to the first theme before dying away.[32]

III. Adagio sostenuto

[edit]

The slow movement is centred on F♯ minor, which is a third interval down from the B♭ major key of the first two movements.[33] It is Beethoven's longest slow movements[34] (e.g. Wilhelm Kempff played for approximately 16 minutes and Christoph Eschenbach 25 minutes). The movement has been called, among other things, a "mausoleum of collective sorrow",[35] Paul Bekker called the movement "the apotheosis of pain, of that deep sorrow for which there is no remedy, and which finds expression not in passionate outpourings, but in the immeasurable stillness of utter woe".[36] Wilhelm Kempff described it as "the most magnificent monologue Beethoven ever wrote".[37]

Structurally, it follows traditional Classical-era sonata form, but the recapitulation of the main theme is varied to include extensive figurations in the right hand that anticipate some of the techniques of Romantic piano music. NPR's Ted Libbey writes, "An entire line of development in Romantic music—passing through Schubert, Chopin, Schumann, Brahms, and even Liszt—springs from this music."[38]

IV. Introduzione: Largo... Allegro – Fuga: Allegro risoluto

[edit]

The movement begins with a slow introduction that serves to transition from the third movement.[39] The transition is achieved by modulating from D♭ major/B♭ minor to G♭ major/E♭ minor to B major/G♯ minor to A major, which modulates to B♭ major for the fugue. Dominated by falling thirds in the bass line, the music three times pauses on a pedal and engages in speculative contrapuntal experimentation, in a manner foreshadowing the quotations from the first three movements of the Ninth Symphony in the opening of the fourth movement of that work.

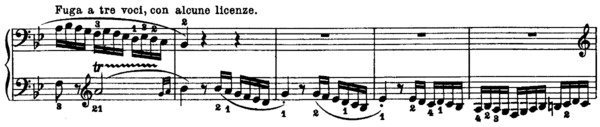

After a final modulation to B♭ major, the main substance of the movement appears: a three-voice fugue in 3

4 meter.[40] The subject of the fugue can be divided itself into three parts: a tenth leap followed by a trill to the tonic; a 7-note scale figure repeated descending by a third; and a tail semiquaver passage marked by many chromatic passing tones, whose development becomes the main source for the movement's unique dissonance. Marked con alcune licenze ("with some licenses"), the fugue, one of Beethoven's greatest contrapuntal achievements, as well as making tremendous demands on the performer, moves through a number of contrasting sections and includes a number of "learned" contrapuntal devices, often, and significantly, wielded with a dramatic fury and dissonance inimical to their conservative and academic associations. Some examples: augmentation of the fugue theme and countersubject in a sforzando marcato at bars 96–117, the massive stretto of the tenth leap and trill which follows, a contemplative episode beginning at bar 152 featuring the subject in retrograde, leading to an exploration of the theme in inversion at bar 209.[41]

Influence

[edit]The work was perceived as almost unplayable but was nevertheless seen as the summit of piano literature since its very first publication. Completed in 1818, it is often considered to be Beethoven's most technically challenging piano composition[42] and one of the most demanding solo works in the classical piano repertoire.[43][44]

The Piano Sonata No. 1 in C, Op. 1 by Johannes Brahms opens with a fanfare similar to the fanfare heard at the start of the Hammerklavier sonata.

Felix Mendelssohn's Piano Sonata in B♭ major, Op.106, is thought to have been influenced by the Hammerklavier sonata,[45] although the shared Opus number is coincidental. Mendelssohn's sonata has a similar opening fanfare in B♭ major, with a secondary theme in G major. The sonata's second movement is also a scherzo in 2

4, and its third movement contains a transition into the fourth.[46]

Orchestration

[edit]The composer Felix Weingartner produced an orchestration of the sonata in 1930.[45] In 1878, Friedrich Nietzsche had suggested such an orchestration:

In the lives of great artists, there are unfortunate contingencies which, for example, force the painter to sketch his most significant picture as only a fleeting thought, or which forced Beethoven to leave us only the unsatisfying piano reduction of a symphony in certain great piano sonatas (the great B flat major). In such cases, the artist coming after should try to correct the great men's lives after the fact; for example, a master of all orchestral effects would do so by restoring to life the symphony that had suffered an apparent pianistic death.[47]

However, Charles Rosen considered attempts to orchestrate the work "nonsensical".[48]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Kinderman 2009, p. 219.

- ^ Hector Berlioz (12 June 1836). "Listz". Revue et gazette musicale de Paris (in French). 3 (24): 198–200.

- ^ a b Morante 2014, p. 238.

- ^ a b Cooper 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Morante 2014, p. 246.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 281.

- ^ Morante 2014, p. 240.

- ^ Kinderman 2009, p. 223.

- ^ Cooper 2017, p. 170.

- ^ Tyson 1962, p. 236.

- ^ Tyson 1962, p. 237.

- ^ Lockwood 2003, p. 384.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 228.

- ^ Lockwood 2003, p. 377.

- ^ a b Marston 1991, p. 404.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 280-281.

- ^ Kinderman 2008, p. 120.

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 409.

- ^ Crumey, Andrew. "Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata". Retrieved 24 July 2023.

- ^ Cooper 2017, p. 171.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 218.

- ^ Morante 2014, p. 257.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 219.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 221.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 228.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 222.

- ^ Badura-Skoda, Paul (2012). "Should We Play a♮ or a♯ in Beethoven's "Hammerklavier" Sonata, Opus 106?". Notes. 68 (4): 751–757. ISSN 0027-4380. JSTOR 23259642.

- ^ Wen 2015, p. 146-147.

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 423.

- ^ a b c Rosen 2002, p. 223.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 235.

- ^ Rosen 2002, p. 224.

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 424.

- ^ Cooper 2008, p. 282.

- ^ Wilhelm von Lenz, quoted in Libbey 1999, p. 379

- ^ Bekker, Paul (1925). Beethoven (translated and adapted by Mildred Mary Bozman). J. M. Dent & Sons, p. 134.

- ^ Schumann, Karl. Beethoven's Viceroy at the Keyboard in Celebration of Wilhelm Kempff's Centenary: His 1951–1956 Recordings of Beethoven's 32 Piano Sonatas.

- ^ Libbey 1999, p. 379.

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 426.

- ^ Tovey 1976, p. 243.

- ^ Willi Apel, "Retrograde," Harvard Dictionary of Music (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1969), p. 728.

- ^ Staines & Clark 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Hinson 2000, p. 94.

- ^ Lederer 2011, p. 105.

- ^ a b Morante 2014, p. 253.

- ^ Larry Todd, R (2022). "Piano Sonata in B flat major, Op 106 (Mendelssohn) - from CDA68368 - Hyperion Records". www.hyperion-records.co.uk. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Human, All Too Human, § 173

- ^ Rosen 1997, p. 446.

Sources

[edit]- Cooper, Barry (2008). Beethoven. The master musicians. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531331-4. OCLC 166314843.

- Cooper, Barry (2017). The creation of Beethoven's 35 piano sonatas. Ashgate Historical Keyboard Series. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315615080. ISBN 978-1-4724-1433-5.

- Hinson, M. (2000). Guide to the pianist's repertoire (3rd ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-253-33646-5.

- Libbey, Theodore (1999). The NPR Guide to Building a Classical CD Collection. New York: Workman Publishing. ISBN 0-7611-0487-9. OCLC 42714517.

- Lederer, Victor (2011). Beethoven's piano music: a listener's guide. Unlocking the masters series. Milwaukee: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-194-0.

- Marston, Nicholas (Autumn 1991). "Approaching the Sketches for Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata". The Journal of the American Musicological Society. 44 (3): 404–450. doi:10.2307/831645. JSTOR 831645.

- Morante, Basilio Fernández (2014). "A Panoramic Survey of Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata, Op. 106: Composition and Performance". Notes. 71 (2). Translated by Davis, Charles: 237–262. doi:10.1353/not.2014.0152. ISSN 1534-150X. JSTOR 44734880.

- Kinderman, William (2008). "The piano music: concertos, sonatas, variations, small forms". In Stanley, Glenn (ed.). The Cambridge companion to Beethoven. The Cambridge companions to music (5 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58074-8.

- Kinderman, William (2009). Beethoven (2 ed.). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532825-7. OCLC 173136168.

- Rosen, Charles (1997). The Classical Style: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven (expanded ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. pp. 409–433. ISBN 978-0-393-04020-3.

- Rosen, Charles (2002). Beethoven's Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion. Yale University Press. pp. 218–228. ISBN 978-0-300-09070-3. JSTOR j.ctt5vm67n.

- Rosenblum, Sandra P. (1988). "Two Sets of Unexplored Metronome Marks for Beethoven's Piano Sonatas". Early Music. 16 (1): 59–71. ISSN 0306-1078. JSTOR 3127048.

- Staines, J.; Clark, D., eds. (July 2005). The Rough Guide to Classical Music (4th ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84353-247-7.

- Tyson, Alan (1962). "The Hammerklavier and Its English Editions". The Musical Times. 103 (1430): 235–7. doi:10.2307/950547. JSTOR 950547.

- Tovey, Donald Francis (1976). A companion to Beethoven's pianoforte sonatas: Complete analyses (Reprint ed.). New York: AMS Press. ISBN 978-0-404-13117-3.

- Wen, Eric (2015). "A Sharp Practice, A Natural Alternative: The Transition into the Recapitulation in the First Movement of Beethoven's "Hammerklavier" Sonata". In Beach, David; Goldenberg, Yosef (eds.). Bach to Brahms: essays on musical design and structure. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-515-1.

External links

[edit]- Piano Sonata No. 29: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Sonata for piano (B-flat major) Op. 106", Work details, sound files, sketches, manuscripts, editions; Beethoven House, Bonn

- A lecture by András Schiff on Beethoven's piano sonata Op. 109, Part One, Part Two